Introduction to polymers

The word polymer comes from Greek. It’s a compilation of poly-, meaning many and meros meaning parts. It indicates that we deal with large molecules, or macromolecules. Their mere size governs how they interact with one another and their neighbours. This is referred to as intra- and intermolecular forces, where covalent bond is the normal intramolecular force that ties the polymers together. Intermolecular forces are what makes the polymers interact with one another. In polymeric materials it is usually van der Waal’s (also called London dispersion forces), dipole-dipole or hydrogen bonding.

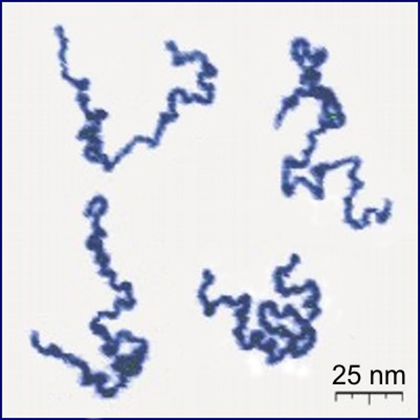

Figure 1: Atom force microscopy image of actual dissolved polymers (Roiter, Y. and Minko, S. AFM Single Molecule Experiments at the Solid-Liquid Interface: In Situ Conformation of Adsorbed Flexible Polyelectrolyte Chains, Journal of the American Chemical Society, vol. 127, iss. 45, pp. 15688-15689 (2005)) Wikimedia / CC BY-SA 3.0

Polymers are by no means a recent manmade invention. Evolution has formed lots of different polymers and continues to do so. Deoxyribonucleic acid, most often abbreviated DNA, that carries information about living matter, is in fact a polymer. There are many other polymers in nature, cellulose in all green plants, proteins in animals, enzymes to facilitate chemical processes, latex from the rubber tree and many more.

You may think that the design of synthetic polymers was inspired by nature, but that was not the case. Rather, chance ruled when rubber was cross-linked by sulphur or when Bakelite was formed by impregnating sawdust with phenol-formaldehyde. It was not until the 1920s that the pioneering work of Hermann Staudinger changed the minds of the scientific community to accept the macromolecular concept. From there on it became essential to be able to define and describe polymers.

There are three key concepts to describe polymers:

- constitution

- configuration

- conformation.